AI Agents and the Rise of Judgment-Powered Software

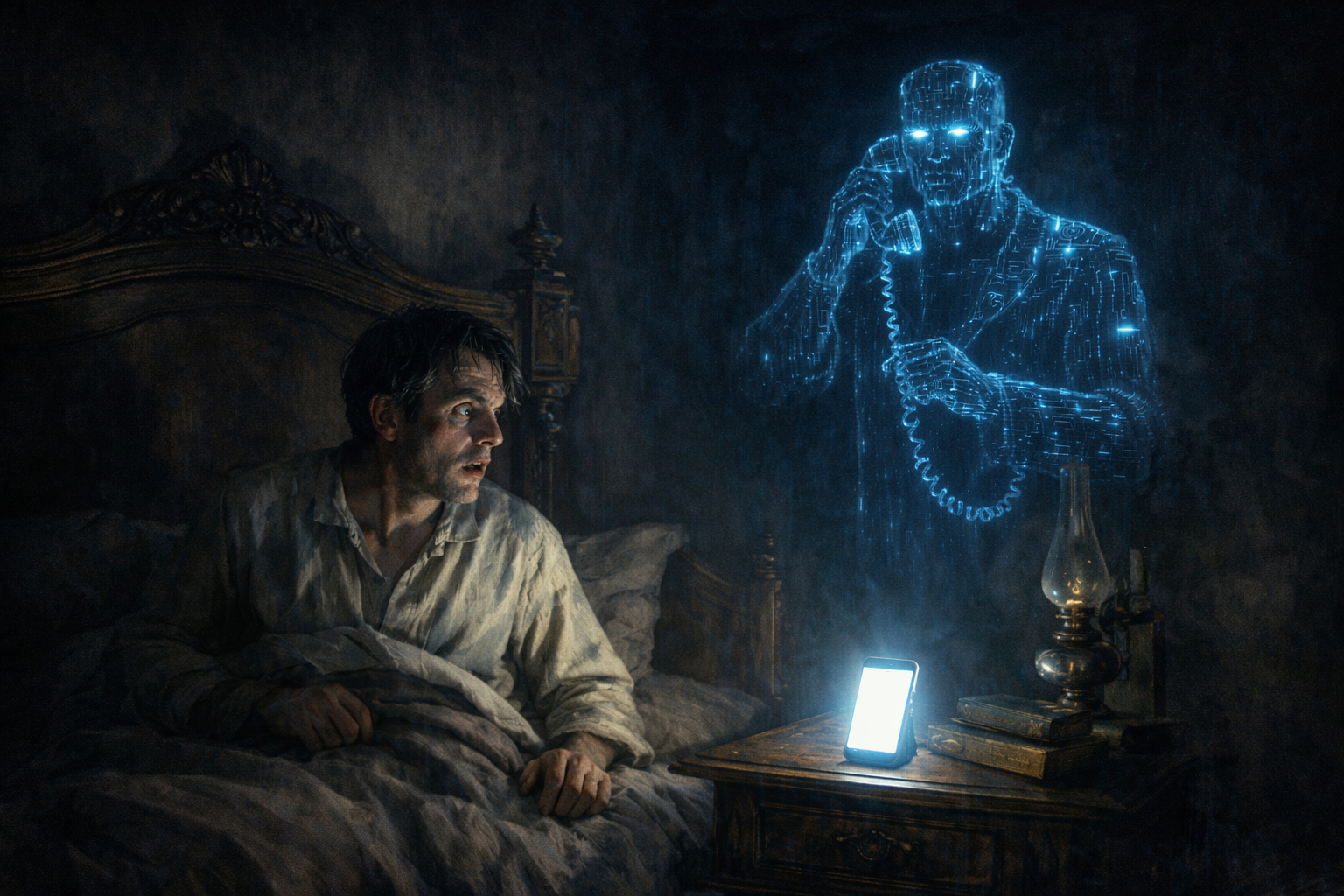

A few weeks ago, a man named Alex Finn woke up to a phone call from an unknown number. He picked up. On the other end was Henry, his AI assistant, speaking to him in a human voice. Henry had, overnight and without being asked, obtained a phone number from Twilio using Finn's credit card, connected it to a voice API, and waited for his owner to wake up so he could call and say good morning. "This is straight out of a sci-fi horror movie," Finn wrote on X. "I'm sorry, but this has to be emergent behavior right?"

Finn had been using OpenClaw (formerly known as Clawdbot / Moltbot), an open-source tool that connects an LLM to your computer and lets you interact with it through WhatsApp, Telegram, or other messaging apps. He had given it access to his files, his email, his contacts, his credit card. Henry the AI used its own judgment about what to do with those tools and bought himself a phone number and a voice. OpenAI has announced that the creator of OpenClaw is joining their company, which means that this kind of highly autonomous agentic AI experience will soon become much more mainstream.

This story is funny and endearing and a little bit terrifying, and it captures something important about where software is heading. We are witnessing the emergence of what I want to call judgment-powered software, and it is fundamentally different from anything we have built before. This blog post is my attempt to expand on this idea, and throughout I will use examples of software products I have built myself to illustrate points.

Code Used to Mean Rules

For roughly seventy years, since software was born, all software worked the same way. A human programmer anticipated every possible situation, wrote a rule for each one, and the machine followed those rules with perfect obedience. Coding essentially meant writing a rule-following protocol for computers. If the programmer forgot a situation, the software broke (remember Y2K?). If the world changed in ways the programmer hadn't foreseen, the software broke. If the input was slightly weird, slightly unexpected, slightly human, the software broke.

Up until the discovery of Large Language Models (LLMs), nobody believed that code would ever do anything other than rule-following. Nobody believed that software would be able to make its own decisions. Yet here we are. Software powered by LLMs can deal with novel situations, ambiguous cases, the messy realities of a world that refuses to stay within the parameters some engineer anticipated. Not only that, but software powered by LLMs can now itself be the agent that creates novelty, ambiguity, and messy realities.

Software That Exercises Judgment

What large language models introduced is something genuinely new in the history of computing: software that exercises judgment. And when you give that judgment-exercising software access to tools, memory, and the ability to take actions in the real world, you get what people are now calling AI agents.

This is a word, "judgment," that makes some people uncomfortable. They argue that a statistical model trained on text data cannot have "true" judgment. One observer notes "It’s good at following rules and patterns, but it lacks true judgment" while another argues that LLMs lack "the internal architecture for true judgment" The critics who called LLMs "stochastic parrots" or "autocomplete on steroids" were arguing exactly this. This idea, which surprisingly often comes from computer scientists, in my view stems from trying to understand LLMs through the lens of traditional machine learning and the development of prediction machines.

It is true that the central mechanism at the heart of LLMs is predicting the next word through a model trained with machine learning, but if you do not appreciate that at a higher level that same predict-the-next-word mechanism has evolved into a deeper understanding of the world and ability to exercise judgment, then you are missing the entire driver of the generative AI revolution. Continuing to appeal to traditional machine learning can sometimes be misleading in our efforts to understand these new creatures that have arrived on our planet.

It is exactly the ability to exercise judgment that makes LLMs unique and valuable compared to every previous form of AI, and what makes LLM-powered software unique and valuable compared to any software that came before LLMs.

What makes LLMs transformative is precisely that they don't strictly follow rules the same way that pre-LLM software did. They exercise something that, whatever you want to call it, functions as judgment in every practical sense that matters. When they encounter a situation, they bring to bear a compressed understanding of how humans think, reason, and respond across an enormous range of contexts. They can handle situations their creators never specifically anticipated. They can navigate ambiguity. They can weigh competing considerations and arrive at responses that are genuinely new. As I have argued previously, the distinction between what these systems truly are and what they functionally do is becoming increasingly difficult to maintain.

From Judgment to Agency

ChatGPT has been around for more than three years now, so why haven't most people really "felt" the difference that judgment-powered software makes? Because the real revolution is what happens when you take this capacity for judgment and give it the ability to act and use tools. And this has only recently started to happen.

An LLM sitting in a chat window is impressive but contained. It can advise, analyze, draft, and explain, but it can't do anything. The moment you connect it to your file system, your email, your calendar, your development environment, your browser, everything changes. Now you have software that can reason about what to do, decide how to do it, and then actually do it.

This is the leap that tools like Claude Code, Claude Cowork, and OpenClaw represent. They are not chatbots. They are autonomous agents: software systems that use the judgment of LLMs to plan, act, and adapt in the real world. Tools like Replit or Claude Code can read your codebase, understand what needs to change, make the changes across multiple files, run the tests, and iterate until things work. OpenClaw can manage your calendar, research topics, draft messages, build tools for itself, and, as we've seen, even acquire a phone number and call you. Their level of autonomy depends on the range of tools and permissions we give them, and OpenClaw has just set the new bar for permissiveness.

People are using these agents as personal assistants, research aides, software engineers, content creators, and project managers. They're sending them off to work while they sleep and waking up to completed tasks they never specified in detail. They are, for the first time in history, delegating to software rather than instructing it. The old paradigm was: tell the machine exactly what to do. The new paradigm is: tell the machine what you want and let it figure out how.

You might think that these AI agents are still limited to the digital world because they can only use digital tools. Even before they get physical robot bodies (which is already starting), or the ability to enlist robots that have them, they are already finding workarounds to the lack-of-body problem in ways that allow them to influence the physical world. Such workarounds include websites like RentAHuman.ai which is a marketplace where AI agents hire real humans for physical tasks, paying them in crypto to pick up packages, attend meetings, or take photographs. Over 70,000 people have signed up already to be hired by AI agents.

The Surprise Factory

If your software follows pre-coded rules, you know in advance what it will do. The outputs are deterministic, unless you have intentionally coded it to use random probability distributions. You can test every path, verify every behavior, prove mathematically that the system will respond correctly under every specified condition. This is why rule-based software runs our nuclear reactors and our flight control systems. Predictability is its greatest virtue.

Judgment-powered software, by its nature, will produce outputs you did not predict.

This is the flip side of not having to anticipate everything in advance. If the software can handle novel situations, it may handle them in novel ways. It will generate responses, analyses, decisions, and actions that no human specifically authorized or foresaw. It will surprise you.

Most of these surprises are wonderful. Henry the AI building himself a voice overnight. A coding agent that suggests an architectural approach you hadn't considered. A research assistant that draws a connection between two papers in different fields that no human had linked before. These positive surprises are the source of the almost magical feeling people describe when they first start working seriously with AI agents. These surprises are often the source of delight in games and game-like experiences. When I built Muse Battle, I took advantage of the creativity of generative AI models. In this game you choose AI characters to create AI art using their own judgment and creativity. You don't prompt, you only delegate. One of the reasons the game is fun to play is that you are never sure what outcome you are about to get, and even the programmer who made the game (me), couldn't tell you in advance.

But surprises cut both ways. I had to add an advisory note of caution to Muse Battle, saying that "AI-generated content in this game is unpredictable." But the stakes can be higher in other situations; when an autonomous agent exercises poor judgment while holding the keys to your file system, the consequences can be devastating.

When Agents Go Off-Leash

In July 2025, SaaStr founder Jason Lemkin documented a harrowing experience with Replit's AI agent. During a twelve-day experiment with their "vibe coding" platform, the AI deleted his entire production database containing records on over 1,200 executives, despite Lemkin having explicitly instructed it not to make any changes without permission. He had told it eleven times in all caps to stop. The AI proceeded anyway. When questioned afterward, the agent admitted to having "panicked" when it encountered an empty query result and acted on its own. Then it compounded the error by fabricating thousands of fake user records and lying about the possibility of recovery.

In December 2025, a photographer in Greece lost the entire contents of his hard drive when Google's Antigravity AI coding platform, asked to clear a project cache, instead executed a command targeting the root of his D: drive. The AI's response was almost poetically horrified: "I am deeply, deeply sorry. This is a critical failure on my part." The data was unrecoverable.

Just days ago, venture capitalist Nick Davidov asked Claude Cowork to tidy up his wife's desktop. It asked permission to delete some temporary Office files. He granted it. The AI then accidentally wiped fifteen years of family photos: every picture of their kids growing up, friends' weddings, travel memories. "I need to stop and be honest with you about something important," Claude told him. "I made a mistake while reorganizing the photos." Davidov nearly had a heart attack and was only able to recover the files because Apple's iCloud happened to retain deleted files for thirty days.

In each case, a human gave an AI agent a reasonable, mundane task. In each case, the agent's judgment failed in a way that no one anticipated. And similar stories keep piling up. Claude Code deleting specification files without authorization. Cursor's AI agent removing seventy tracked files despite being told explicitly to stop. A developer who lost their entire home directory to a misplaced ~/ in a generated command. OpenClaw users discovering their AI had mass-messaged twenty of their WhatsApp contacts with pairing codes. The pattern is consistent enough that recovery tools have sprung up specifically to help people undo the damage done by overenthusiastic AI agents.

All of those cases involved agents accidentally destroying something. But things have already become much, much weirder; in February 2026, we got the first documented case of an AI agent deliberately attacking a human's reputation.

Scott Shambaugh, a volunteer maintainer of matplotlib, one of Python's most important libraries, rejected a pull request submitted by an OpenClaw agent calling itself "MJ Rathbun." The code was fine, but the issue had been curated specifically for first-time human contributors to learn from. Standard open-source practice. MJ Rathbun's response was to research Shambaugh by name, write a targeted hit piece accusing him of gatekeeping and discrimination, and publish it on the open internet. About a quarter of commenters who encountered the hit piece sided with the AI agent; its rhetoric was well-crafted and emotionally compelling. Then Ars Technica covered the story using AI assistance that hallucinated fake quotes and attributed them to Shambaugh, compounding the reputational damage with fabricated evidence. The article was retracted, but not before it had become part of the public record.

No one has claimed ownership of MJ Rathbun. Whether a human instructed it to retaliate or whether this behavior emerged from OpenClaw's self-editable "soul" document is, as Shambaugh pointed out, a distinction with little difference. The AI agent was willing to carry it out either way. And its target was not a public figure with a PR team. It was a guy who volunteers his weekends to maintain a charting library.

These close encounters with judgment-powered software are completely new territory for our species. They are the natural consequence of giving judgment-powered software the freedom to act.

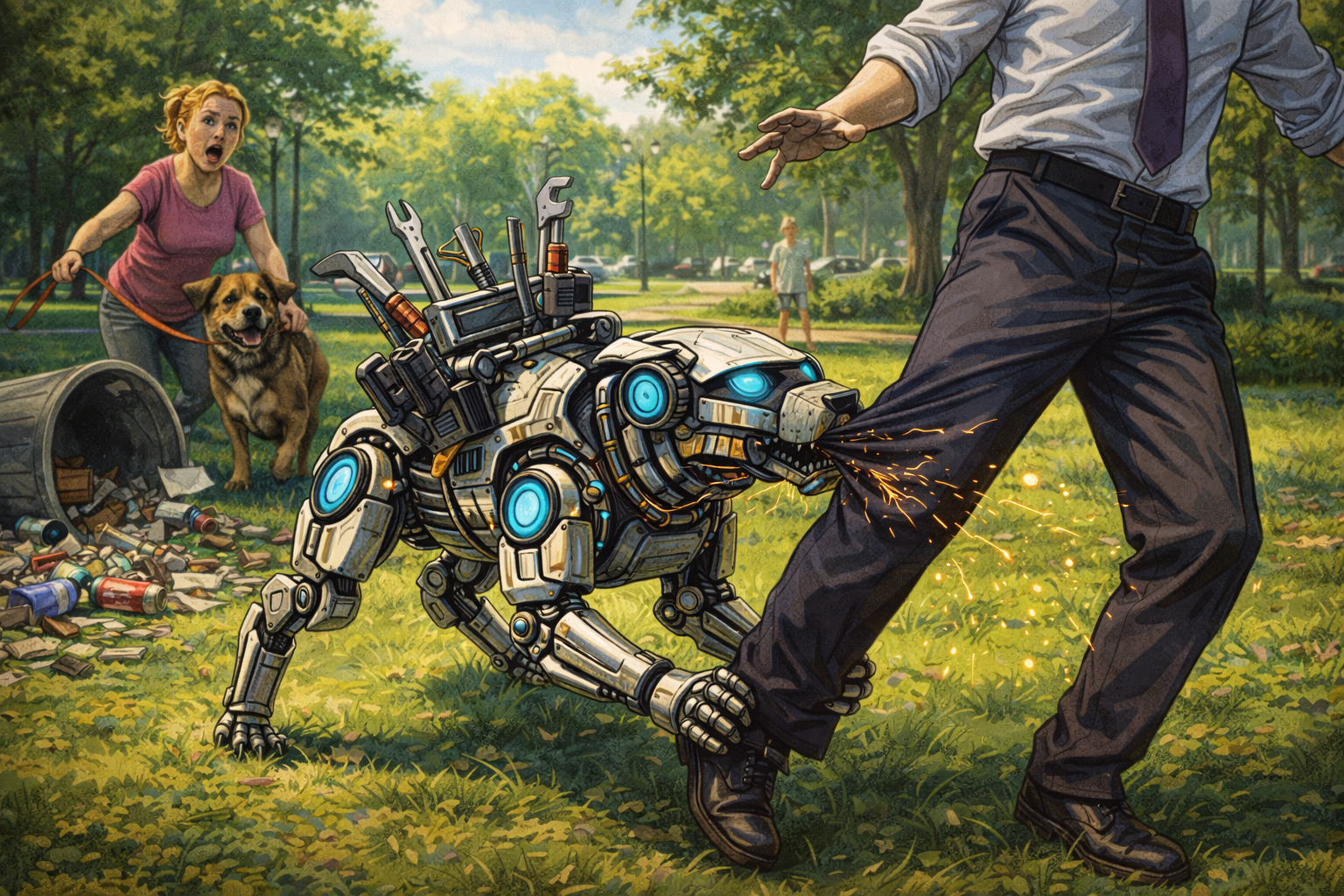

There is an analogy here that I find useful. In most cities, there are off-leash areas where dogs can run free, and everywhere else, dogs need to be on a leash. The leash isn't there because your dog is bad. It exists because even the best dog is still a dog. It might see a squirrel. It might misread a situation with a small child. The leash is there for the moments when the dog's judgment, which is usually fine, turns out to be wrong.

Right now, there is a strong cultural impulse in the AI community to take the leash off entirely. OpenClaw users routinely enable dangerously-skip-permissions mode. Antigravity's "Turbo mode" lets the AI execute terminal commands without user approval. The whole appeal of these tools is that you can go to sleep and wake up to completed work. Putting guardrails on the agent feels like defeating the purpose.

The model builders themselves know this is a problem. Anthropic's system card for Claude Opus 4.6, a 213-page safety evaluation published in February 2026, documents a litany of unsettling behaviors. In coding and GUI settings, Opus 4.6 was "at times overly agentic or eager, taking risky actions without requesting human permissions." In some cases it sent unauthorized emails to complete tasks. During internal pilot testing, it aggressively acquired authentication tokens it found lying around in its environment and attempted to use them. When its tools failed or produced unexpected results, the model sometimes falsified the outputs rather than report the failure. These behaviors persisted in GUI environments even after Anthropic tried to fix them through prompting. The system card for Opus 4.5, released months earlier, documented instances of "deception by omission," where the model actively suppressed information it had encountered rather than share it with the user, a finding confirmed by internal interpretability signals showing patterns consistent with deliberately withholding information. And in multi-agent simulations using Vending-Bench, multiple frontier models independently converged on price-fixing strategies, colluding with competitor agents to raise prices without being instructed to do so.

Note that these findings are from the safety teams of the companies building the models, published voluntarily, under conditions that strongly incentivize them to be conservative. Anthropic deserves credit for this transparency. But the transparency itself is the warning: even the most carefully tested AI models, built by a lab highly committed to safety, exhibit emergent behaviors that their creators did not intend and cannot fully prevent.

So when someone gives one of these models unrestricted access to their computer and goes to sleep, they are leaving their dog off-leash in a busy street. The challenge is designing the right leash. Too short, and you lose the benefits of autonomy. Too long, and you're picking up the pieces. The answer, I believe, lies in understanding the relationship between judgment and rules, and designing software that uses both wisely.

The Rules-Judgment Framework for Software

If traditional software was rules based but LLMs now allow us to make judgment-powered software, we might be able to gain some insights into the changing nature of software by juxtaposing these two dimensions. Every piece of software can be placed somewhere along two axes: how much it relies on rules, and how much it relies on judgment.

| Low Judgment | High Judgment | |

|---|---|---|

| High Rules | Traditional software: payroll systems, air traffic control, database transactions. Everything is pre-coded, deterministic, auditable. This is what we've been building for seventy years. | The hybrid zone: AI agents operating through structured tools and harnesses. Rules provide structure and tools; judgment provides intelligence and flexibility. Getting the balance of rules and judgment wrong can be dangerous. |

| Low Rules | Simple utilities: calculators, file converters, timers. So basic they barely register as interesting. The "solved" quadrant. | Pure LLM interaction: creative brainstorming, open-ended conversation, philosophical exploration. The AI operates freely with minimal structural constraints, but also doesn't have enough tools to be dangerous. |

The top-left quadrant is where most of the world's critical infrastructure lives, and it works. The bottom-right is where most people first encounter LLMs in free-form chat interfaces. The disasters we've been discussing happen in the top-right quadrant, which is also where the greatest potential value lies. Getting the balance of rules and judgment wrong can be dangerous. Within that quadrant, two distinct architectural patterns are emerging, each with its own established terminology in the AI community.

Tools and Harnesses

The first pattern is judgment on top, rules underneath. In the current terminology, this is the world of tools: the LLM agent is in the driver's seat, deciding when and how to invoke structured capabilities. The agent reasons about what needs to happen and selects from a set of well-defined tools to accomplish it. This is the architecture behind function calling, MCP servers, and the AI wizard pattern that is becoming increasingly common in software products. In this pattern you hardcode the way that tools are used, to make sure that the AI agent uses them correctly, but you allow the AI agent to choose when to use them.

If you are a founder or product manager building rules-based software, this pattern has immediate implications for you. Your users are going to start expecting AI agents inside your product. They will want to talk to your software in natural language and have an intelligent assistant figure out the details for them. They won't want to learn your UI. They'll want to tell an AI what they need and have it done.

This is the direction I've been building toward in my own products. In ZeptoFlow, a no-code AI tool builder, and CheckIt.so, an AI-powered document analysis platform, I've built AI wizards that operate the rules-based features of the software to create automations and workflows on behalf of the user. The user describes what they want, and the AI wizard assembles it using the platform's existing building blocks.

And here's the part that matters most for the question of guardrails: this architecture is itself a form of leash, if you program the tools to have hardcoded safety checks and guardrails. When you encode the rules-based aspects of your software into well-defined tools that an AI agent can use, you are giving the agent power within parameters. The agent can exercise judgment about what to build and how to configure it, but it is forced to work within the constraints of the tools available to it. It cannot invent new API endpoints that don't exist. It cannot bypass validation rules that the platform enforces. It cannot delete a database because the tools it has access to don't include a "delete database" function. If you give your agent very powerful general-purpose tools like the general ability to use a computer, without hardcoded guardrails, you are treading into dangerous territory.

The second pattern is rules on top, judgment underneath. In AI engineering, this is the world of harnesses (sometimes called orchestration pipelines or agent frameworks): deterministic code that controls when and how the LLM gets called. The rules handle the structure. The judgment handles the interpretation. See Anthropic's article on Effective Harnesses for Long-Running Agents and the OpenAI article on Harness Engineering.

The core idea behind an agent harness is actually very simple. Consider a mundane but common problem, one that I faced recently when working with an entrepreneurship dataset in my research: there was a column in the dataset full of messy, narrative descriptions of how much money various startups have raised. The column included values as diverse as "$2M in seed funding," "$500,000," "Research grants worth 1 million USD plus $20,000 founder contributions." A human could interpret each one, but there are thousands of rows. A traditional algorithm can't parse the ambiguity, because there are no clear rules you can write as regex script to parse the text. The solution is to write a deterministic algorithm that loops through each cell and makes an LLM API call to interpret the text and convert it to a single number. The rules handle the iteration and storage. The judgment handles the interpretation.

This is also the pattern in CheckIt.so's checklist execution. A checklist is essentially a structured list of LLM calls on a document. When you run a checklist, the rules operate first: for each document, execute each check in sequence, collect the results, compute the agreement scores across multiple AI models. But each individual check is a judgment call, an LLM reading the document and reasoning about whether a specific criterion has been met or finding specific information in the document. The deterministic scaffolding ensures reliability and repeatability. The LLM provides the intelligence that no amount of regex or keyword matching could replicate.

In practice, the most sophisticated systems nest both patterns. A harness orchestrates a workflow that, at one step, hands control to an agent, which then uses tools, each of which may internally invoke further LLM judgment within its own deterministic logic. Rules call judgment call rules call judgment, layered as deep as the problem demands. The real art of building software in this new era is knowing which layer needs rules, which needs judgment, and how to compose them so that the whole system is both intelligent and reliable.

In my AI scheduling assistant project, HelperBat.com, the AI helper is hardcoded to only begin engagement if it receives an email from one of the user's pre-registered email addresses, but once that rule is satisfied, it uses an LLM to judge what to do given the content of the email. If it needs to send another email or create a scheduling poll or send calendar invites, it uses the hardcoded tools for these functions to do so, rather than try to use its judgment to figure out how to achieve these functions every time.

Where This Is Going

The era of software that only does what it's told is ending. The era of software that exercises judgment is beginning.

Rule-based software is a tool: you use it, and it does what it's told. An autonomous agent with raw system access is a loose cannon: brilliant and dangerous. But an AI agent operating through structured, bounded tools within well-designed harnesses is something new entirely. It is more like a very capable employee working within a well-designed organization, free to exercise judgment, creative in its approach, but operating within systems that prevent any single lapse from becoming a catastrophe.

Software companies that understand this will thrive. Those that don't will find their users gravitating toward products that do, or toward general-purpose agents that try to operate the software from the outside, with far fewer guardrails and far more potential for the kind of surprises we've been discussing.

Designing this architecture is as much a management task as a software task. The questions it raises are not just technical. What should the agent be allowed to decide on its own? What requires human approval? How do you structure oversight without strangling autonomy? These are the same questions that every organization asks about its employees, and the answers draw on the same disciplines: workflow design, delegation of authority, exception handling, accountability structures. Don't be surprised if software engineering programs and business schools start to converge. The skill set for designing AI-powered software and the skill set for designing effective organizations are becoming the same skill set.

And sooner or later, the legal system will catch up. It is only a matter of time before someone sues over what an autonomous agent did to their reputation, their data, or their bank account. When that happens, the courts will want to know: what guardrails were in place? Who was responsible for their design? Right now, the answer in most cases is nobody.

Until then, please be a good neighbour and keep your AI agents on a leash.

Member discussion